Back in the good ol’ days before the NCAA was unjustly forced to allow student-athletes to earn compensation for the billions of dollars they generated in ticket sales, television rights, and merchandising, the NCAA released a commercial reminding everyone what college sports is really about:

There are 360,000 NCAA student-athletes and just about all of us will be going pro in something other than sports.

Commercial

What does this have to with economics? Well the same could be said of economics-students as student-athletes: most economics students will get a job in something other than economics.

As a graduate from a ‘Global Top 15’ economics program (whatever that means), I have a decent sense of how many of my classmates went to work in economics or pursue a PhD in economics, however, here’s some quick math to backup my intuition:

Every year roughly 49K and 1K students graduate with a bachelors or post-doctorate degree in economics, respectively. In total there are ~15K individuals employed as economists in the United States. Therefore, there are more than 3x more economics graduates than practicing economists every year. This ratio becomes even more alarming when we consider that there are far fewer economist job openings than 15K (the vast majority of these people aren’t retiring in a given year).

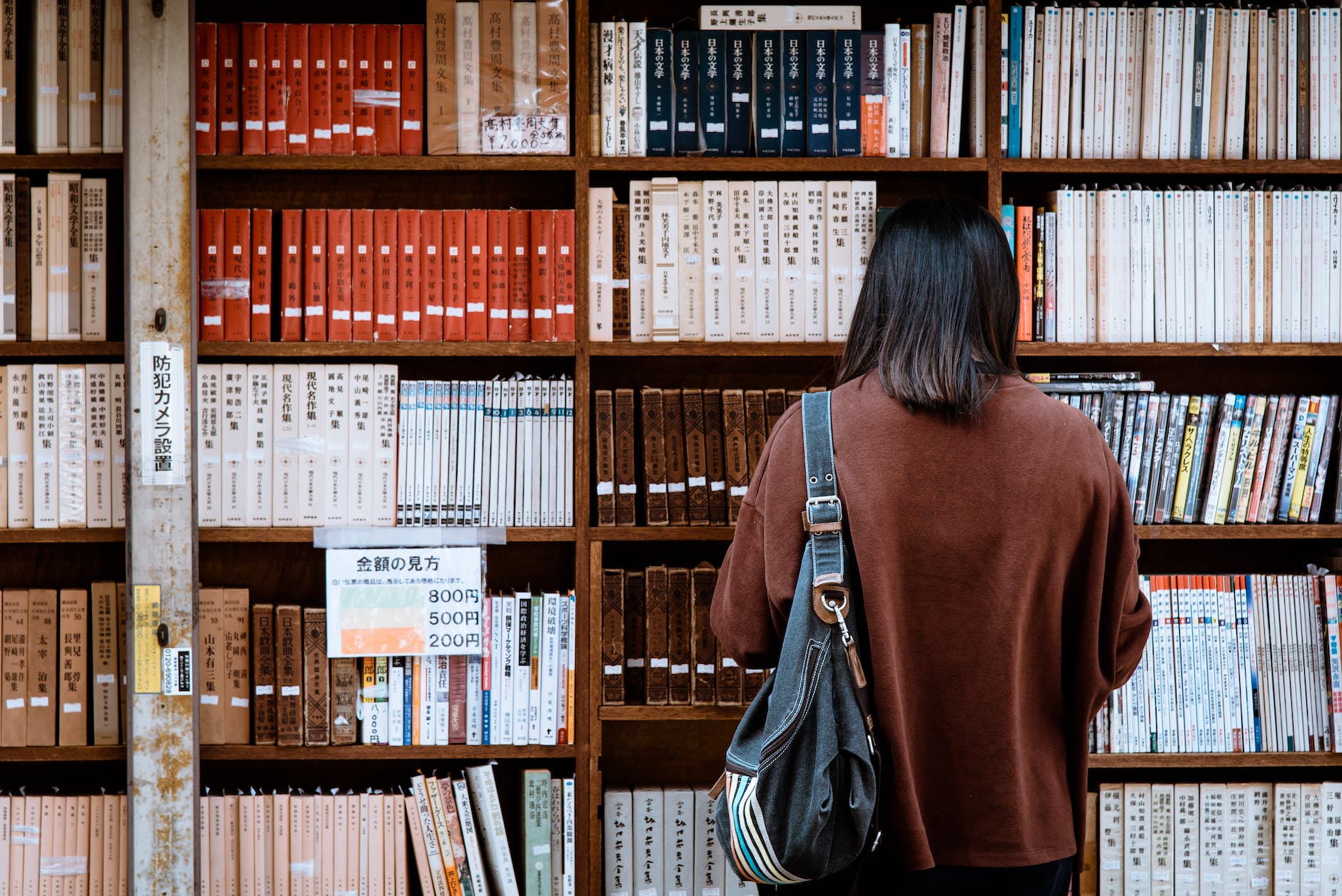

A survey of graduating economics majors from University of Northwestern also lends credibility to this rough analysis:

Obviously these are sectors not roles, but none of these scream ‘economist’. Non-profit/government is probably the closest match, but based on personal experience I’d imagine the vast majority of these people are applying for grants or some other bureaucratic work, both of which are decidedly tasks one does not need an economics degree for…

Fatal Flaws

Now just because someone’s career is in a different field from what they studied does not mean their education was ‘wasted’ or a ‘failure’. Indeed, their education can be viewed as a success since it enabled them to be employed at all. An education also need not be judged solely on it’s earning potential. Learning can be an end in itself, a luxury valued for it’s use, not its usefulness.

And while an education in economics will likely result in a job (outside of economics) or may be enjoyable to study (like it was for me), there are far better ways to spend your time (and massive tuition). I say this because modern, neoclassical economics provides a poor framework to understand the world and an inferior skill-set compared to other disciplines.

This should be obvious in economists inability to predict major economic events such as recessions, inflation surges, and even GDP growth with any degree of reliability.

The general inertness of economics is due to many reasons, but looking in detail at a few fundamental assumptions of the ‘science’ will help provide a better sense of why you probably direct your studies elsewhere.

Note: there are several branches of economics, but we are looking at neoclassical economics in particular because that is what is taught at the vast majority of colleges.

Assumption #1: Perfect information

Neoclassical economics assumes that individuals makes fully informed decisions, meaning an individual knows:

- The quality of goods and services

- The value one will get from a good and service

- All possible alternatives one could spend their money on

It should be painfully obvious that these assumptions are rarely, if ever, true. We buy goods and services without knowing their quality (like a debut album or a haircut from a new barber). We habitually over- or underestimate the value of something to us (like how we compare to averages or a firstborn child). And we have only the foggiest sense of what is possible (think of all the ways you could spend the next hour and you will have only identified a small fraction of what could be).

Assumption #2: Rational actors

Neoclassical economics also assumes that individuals act rationally, that is to say in their best interest. Rationality, however, is often overpowered by emotions, hormones, addiction, herd mentality, and other forces, yet economics largely excludes these factors from any analysis. To be fair, understanding these issues is extremely difficult, but ignoring them often leads to ‘rational’ policies that nonetheless fail, sometimes harmfully, such as globalization (destroying the resiliency of supply chains and independence of strategic industries, and deepening inequality) and low federal interest rates (pricing out future generations from home ownership and eating into savings through inflation).

Assumption #3: measuring value

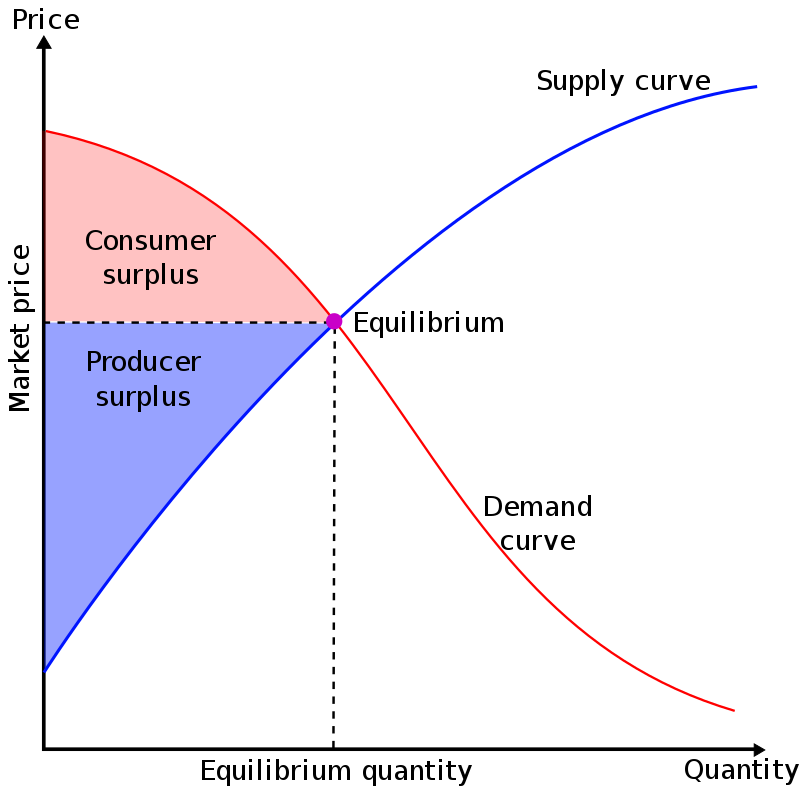

An implicit goal of neoclassical economics is to maximize surplus. There are two components to surplus: consumer surplus and producer surplus. Consumer surplus is measured as the difference between what someone pays for a good/service and how much they would have been willing to pay. Producer surplus is measured as the difference between how much it cost to produce a good/service and how much the good/service sold for. It is usually depicted like so:

There’s nothing technically wrong about this approach, however, it is at odds with common conceptions of justice and common sense. In terms of justice, the ‘standard model’ cares only for the total benefit. There is no consideration of how that benefit is allocated. If someone is unable to pay for a good/service, they have no weight in this methodology. If someone is willing to pay 10x more for a good/service, then that individual is valued 10x more.

In terms of common sense, this methodology only measures value in terms of consumption. The value of preserving the environment is 0. The value of charity is 0. The value of health is 0.

To be fair, in more advanced economics courses these faulty assumptions are relaxed and alternatives are explored, however, what does it say about a discipline that builds on such shaky foundations?

Alternatives

One useful thing that economics taught me was: opportunity cost–any decision must be evaluated in light of alternatives. While economics is by no means ‘all bad’, there are numerous other disciplines that provide a more reliable way to understand the world and/or higher earnings potential. Simply put, there is no reason to study economics other than you really enjoy economics itself (and even that’s not a great reason as I’ll explain later).

Instead of studying make-believe markets, why not study the human mind that gives them life? Why not learn to build the good/services that are the ultimate source of value in markets? Why not study the natural sciences that seek to explain objective reality? Why not create art that delights or expresses the ineffable aspects of the human spirit?

There are numerous fields more worthy of study than economics such as (in no particular order):

- Psychology

- Neuroscience

- Physics

- Art

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Biology

- Chemistry

- Mathematics

It’s worth nothing that all these disciplines were studied by the ancient Greeks (or would have been if the necessary technology was available) and the many of western civilizations best and most beloved ideas are ancient Greek in origin (even if they are dressed in the language of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment).

Counterarguments

A few good ‘economists’

The reason I spend several sunny Saturday afternoons indoors writing this is because I was hurt deeply by economics. And I was only able to be hurt because I had high expectations.

I loved economics because the economists I read had such ‘big’ ideas. Reading Friedrich Hayek, Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen, and many others expanded my mind in ways little else had (this book is an amazing introduction to the most important economic thinkers).

However, I did not recognize it was clever marketing by economics to claim these men. In truth these men were philosophers questioning the fundamental structures of society, justice, and human nature. Contrast that today with economics professors who accept that status quo without quarrel and specialize in minutia (pro tip: many universities publish their research on their website).

Grad School is different

Yes, getting a PhD in economics is different than getting a bachelor’s in economics. The biggest difference is the amount of math, statistics, and programming you’re expected to know such as advanced calculus, differential equations, linear algebra, statistics, and python (if you want to work with unique data sets).

Your success as a graduate student is less determined by your ability to drum up grand new theories while smoking a cigar in a leather chair than your ability to crunch data to determine whether the impact of x on y is 2.3% or 2.6%.

This begs the question of whether it is better to get a undergraduate degree in math than economics…

Sub disciplines

There are dozens of economics sub-disciplines one could study and the hope is that with further specialization things become increasingly applicable. That may be true, but I still argue the vast majority of these sub-disciplines would be better approached from another framework (e.g. psychology, mathematics, philosophy, etc.).

There is, perhaps, one exception: behavioral economics. This is a relatively new field at the intersection of psychology and economics. The quality of the program depends on the school, but the more rooted in psychology and the scientific method, the better.

Are you sure?

As should be abundantly clear I regret formally studying economics in college. I believe most people can scratch their economics itch through casual reading of the greats or approaching economics through a more robust, scientific discipline (as many economics PhDs do).

If you’re undecided, then there are a few other perspectives on this I encourage you to read such as this investigation of econ 101 by Greg Rosalsky, a history of economic failure by Paul Krugman, or this reddit thread.

And if you’ve made it this far with your dreams of studying economics intact, I wish you the best of luck!

Economics graduates what do you think? What do you agree with? Where do you disagree?